This is Why Culture Eats Strategy for Breakfast

Read time: 2-3 minutes

Culture is a hot topic these days. By now, you’re probably familiar with Netflix’s famous 100+ slide deck outlining their corporate values and have enjoyed Simon Sinek’s highly viewed Ted Talk musings on how good leaders make people feel safe. However, it seems we’re hearing ever more about how this elusive dimension of organizational behavior is being embraced by top companies. Why it’s taking root so prominently now I can’t say, though Winston Churchill might have been onto something when he said, “Americans can always be counted on to do the right thing, after they’ve exhausted every other possibility.” That is to say, perhaps companies are now concluding that financial success is, after all, an ensuing result of creating a cultural framework that enables high-quality teams to achieve as opposed to something that is pursued without regard for the softer side of how you get there.

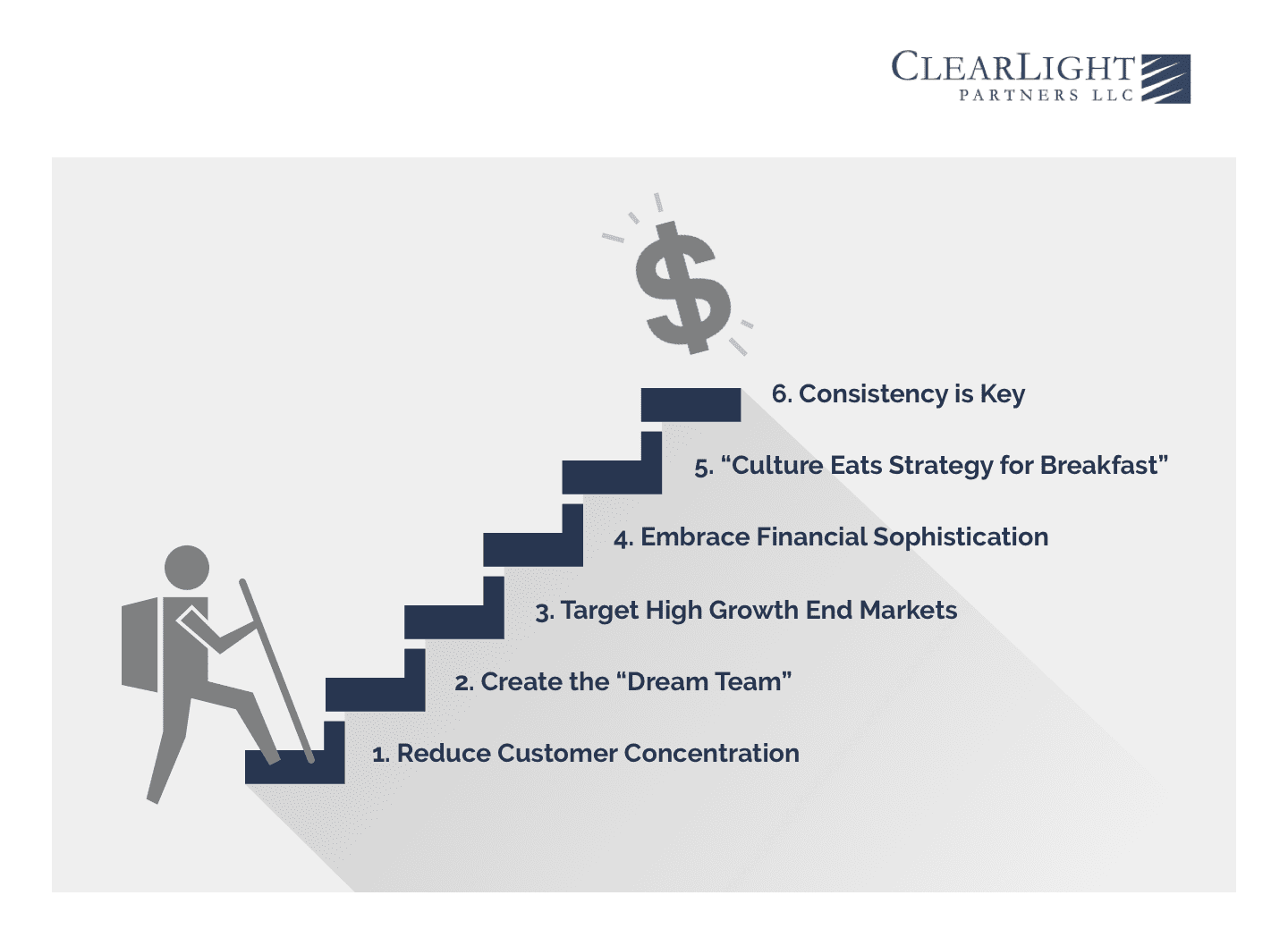

To be clear, this blog is not about how to create a good company culture. There’s been plenty written about that, and I’m still not fully convinced that culture isn’t just a reflection of senior leadership’s behavior and how they reward the cardinal virtues they espouse. What I’d like to explore is why I think that Peter Drucker’s famous, “Culture eats strategy for breakfast” line has withstood the test of time and is presently top of mind for leaders at the helm of companies large and small. To do that, I’ll share the following ways that strong cultural dynamics have contributed to the success of organizations with which I’ve been affiliated. So, without further ado, strong cultures…

- …encourage risk taking that leads to innovation. If the standard of performance is perfection, then people will simply talk themselves out of otherwise good ideas for fear of diminishing their internal status (or worse). However, when it’s OK to make mistakes in the name of progress, employees will take initiative and experiment with new ideas. More often than not, these ideas, while good, won’t move the needle and may even fail. However, without feeling safe enough to try something new, the truly game-changing ideas that allow you to stay ahead of your competition will not come to fruition.

- …allow people to be vulnerable to promote problem solving. If people aren’t comfortable sharing challenges holding them back, then they’ll simply stew in frustration for fear of seeming like they aren’t up to the demands of their job. This will consequently hold the company back from progress it could otherwise be making. However, when people are willing to articulate problems and approach colleagues for advice, then the maxim of two heads being better than one will prevail. True success is when people can be vulnerable in front of a group of peers and/or superiors to access the best of their collective wisdom.

- …reduce the energy wasted on fighting internal battles and focus on beating the competition. In many companies, an employee is forced to fight battles on two fronts – the external (i.e. against the competition), and the internal (i.e. against culture and the agendas of other employees). From my experience, external competitive forces are sufficiently formidable to require complete and undistracted focus. The challenge is that internal struggles are real and often result in a host of counterproductive emotions, most powerfully, worry. I’ll admit that of all the nights I’ve lost sleep in my career, the vast majority have been due to internal issues. Imagine how much stronger your organization would be if 100% of the team’s energy was focused on beating the competition.

- …motivate people to show off their superpowers. This begins with the understanding that each person has a “genius” and that a universal yardstick of ability simply cannot be applied to everyone. If a culture singularly exalts a narrow skillset, then people won’t be energized to exhibit lesser-valued skills that a company may desperately need. There’s a reason it’s beautiful watching cheetahs sprint and dolphins jump acrobatically in the ocean – while different, those behaviors are what those animals are the best at, and they don’t hold anything back. What if observing your team was as fun as watching Blue Planet? Or, better yet, X-Men?

- …speak to the person, not their position, to engender respect throughout the organization. There are hierarchies within every organization and roles that are more glamorous than others. And, usually, people are keenly aware of where their activities stack up in the pecking order of internal respect. One of the faster tactics I’ve seen to demotivate an employee is to engage with them as though their role deserves inferior treatment. Conversely, when a person is treated with respect, regardless of function, it has a way of helping that person find meaning and dignity in their activities which can compound to create unforeseen benefits to the business.

- …recognize achievements that advance important goals. No better way to get a team to keep doing more of what works and less of what doesn’t than to acknowledge strong performance. If this praise comes from the top, you can all but guarantee that others will follow suit. I’ve had bosses make my entire week just by saying “good job” about something I didn’t think they had noticed. All things being equal, happy employees have got to outperform the alternative.

While not an exhaustive list, I can say that I’ve experienced both the good and bad sides of these dynamics. Goes without saying that I’ve functioned at my best when I’ve felt safe enough to innovate, been comfortable asking for help, didn’t worry about internal frictions, knew that my skills were valued, felt respected and received recognition. Interested in your thoughts – how else do strong cultures make employees and companies better?

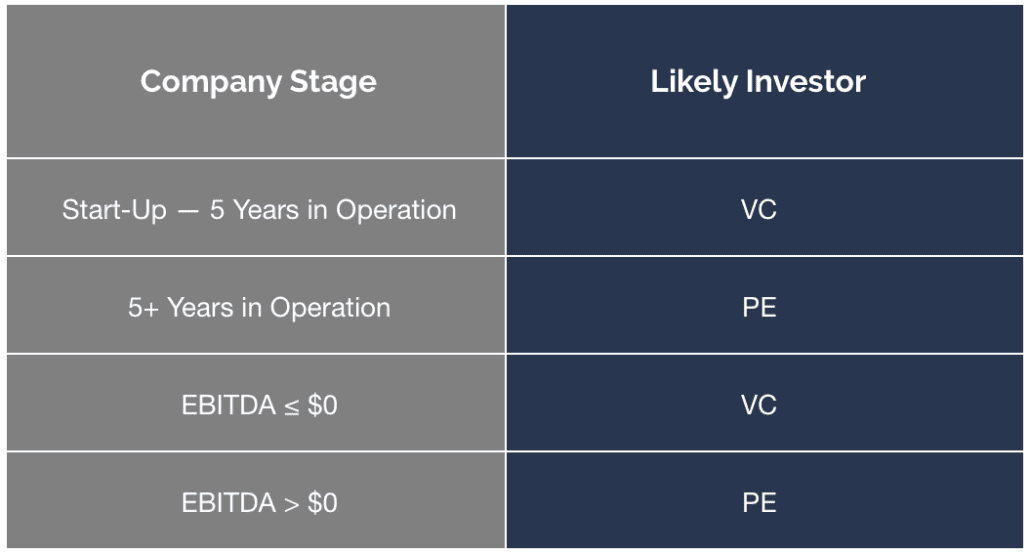

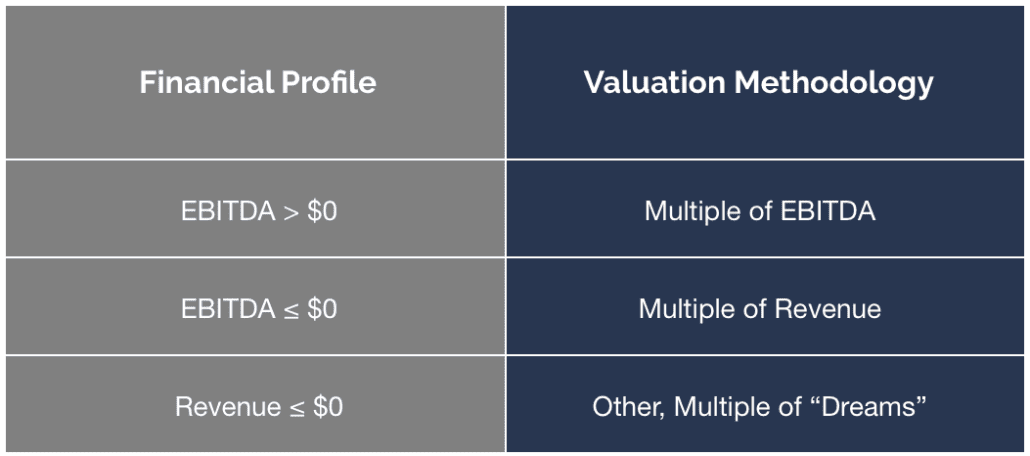

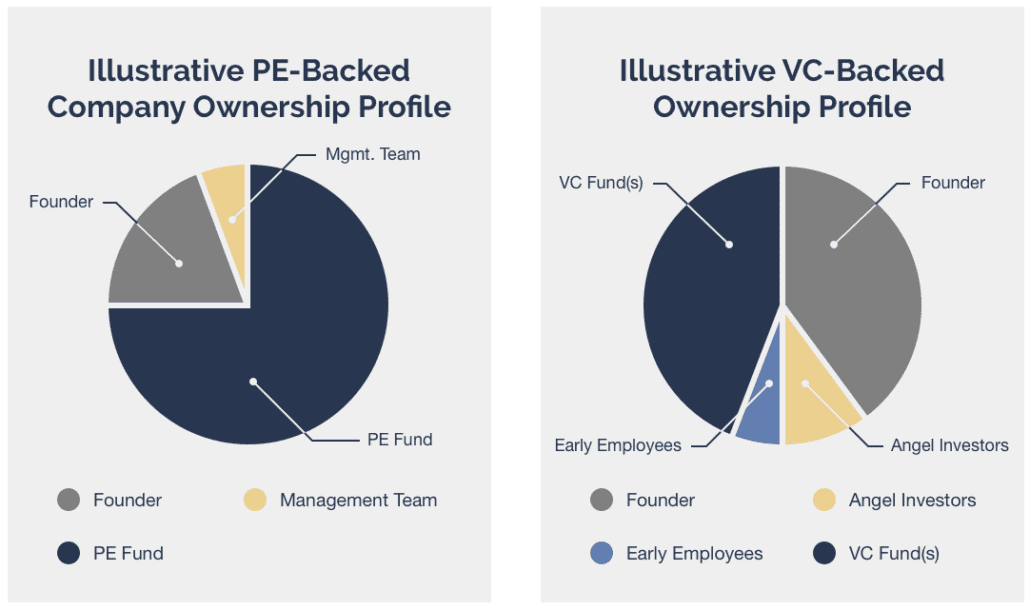

About ClearLight Partners

ClearLight is a private equity firm headquartered in Southern California that invests in established, profitable middle-market companies in a range of industry sectors. Investment candidates are typically generating between $4-15 million of EBITDA (or, Operating Profit) and are operating in industries with strong growth prospects. Since inception, ClearLight has raised $900 million in capital across three funds from a single limited partner. The ClearLight team has extensive operating and financial experience and a history of successfully partnering with owners and management teams to drive growth and create value. For more information, visit www.clearlightpartners.com.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this blog are solely my own and do not necessarily reflect any ClearLight opinion, position, or policy.

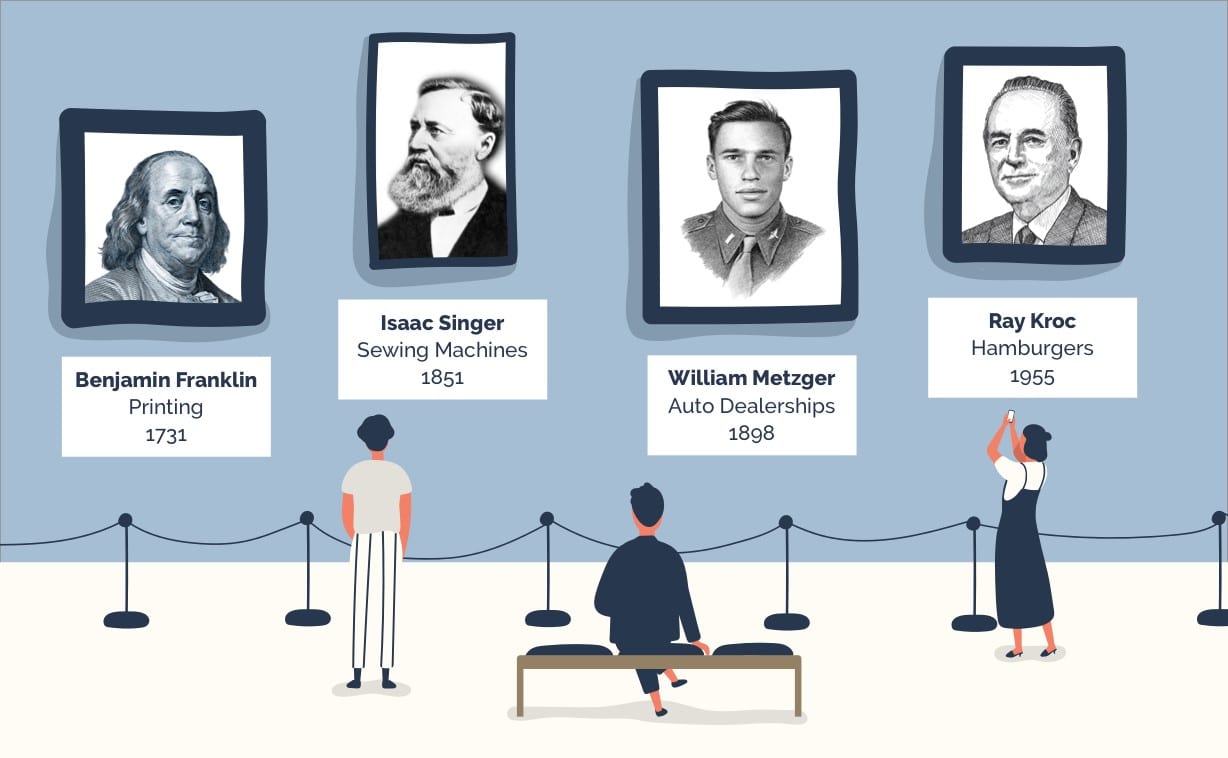

Product or Service that is Staightforward and Can be Consistently Replicated

Product or Service that is Staightforward and Can be Consistently Replicated Product or Service that is Sustainably “On Trend”

Product or Service that is Sustainably “On Trend” Universal Appeal Across Geographies3

Universal Appeal Across Geographies3 Sufficently Long Operating History

Sufficently Long Operating History Critical Mass of Units

Critical Mass of Units Good Unit Economics

Good Unit Economics Successful Franchisees

Successful Franchisees Runway for Future Growth

Runway for Future Growth Build-Out Costs

Build-Out Costs Time to Profitability

Time to Profitability Time to Recoup Build-Out Costs

Time to Recoup Build-Out Costs Time to Maturity

Time to Maturity Mature Revenue, or “Average Unit Volume”

Mature Revenue, or “Average Unit Volume” Mature EBITDA

Mature EBITDA Build-Out Costs / Mature EBITDA

Build-Out Costs / Mature EBITDA Same-Store Sales Growth

Same-Store Sales Growth

1. Public Comps

1. Public Comps 2. Precedent Transactions

2. Precedent Transactions 3. Returns Modeling

3. Returns Modeling 4. Perception of Value

4. Perception of Value