Private Equity vs. Venture Capital: Similar but Mostly Different

Read time: 3-4 Minutes

“The beginning of wisdom is the definition of terms” (Socrates)

Introduction & Definitions of Private Equity and Venture Capital

At 60+ years since the birth of the Private Equity (PE) and Venture Capital (VC) industries, it’s easy to marvel at what they’ve become from their humble beginnings in the 1950’s. While both sectors are now fairly mature, it remains surprisingly commonplace for business owners to use the terms PE and VC interchangeably. Yes, in concept, both are vehicles for capital to flow into private companies with the expectation of returns that beat the public markets, but the differences between these asset classes far outnumber the similarities. So, it seemed time to lay out the primary differentiating factors to eliminate any confusion.

Per Socrates’ advice above, let’s start by providing some basic definitions of PE and VC:

- Private Equity. At its core, private equity is investing into (typically) established private companies to help them grow. To do this, private equity fund managers, or General Partners, will raise capital from Limited Partners that often consist of pension funds, endowments, high net worth individuals or other entities seeking to invest through this asset class. Using this capital, PE funds will source investment opportunities relevant to their investment criteria, negotiate transactions, and work with their acquired companies to improve profitability over what usually amounts to a 3-5 year (or more) investment period.

- Venture Capital. Similar to PE funds, venture capital firms also invest as General Partners on behalf of institutions and other accredited investors. However, they generally focus on emerging companies or technologies that are earlier in their lifecycle and show greater upside potential (described further below).

The Key Differences Between Private Equity and Venture Capital

Based on the definitions above, PE and VC may seem relatively similar at this point, but a closer look will reveal some important distinctions. So, without further ado, here are the main differences between PE and VC. Just remember that the guide below will apply in most cases, but there are exceptions to every rule:

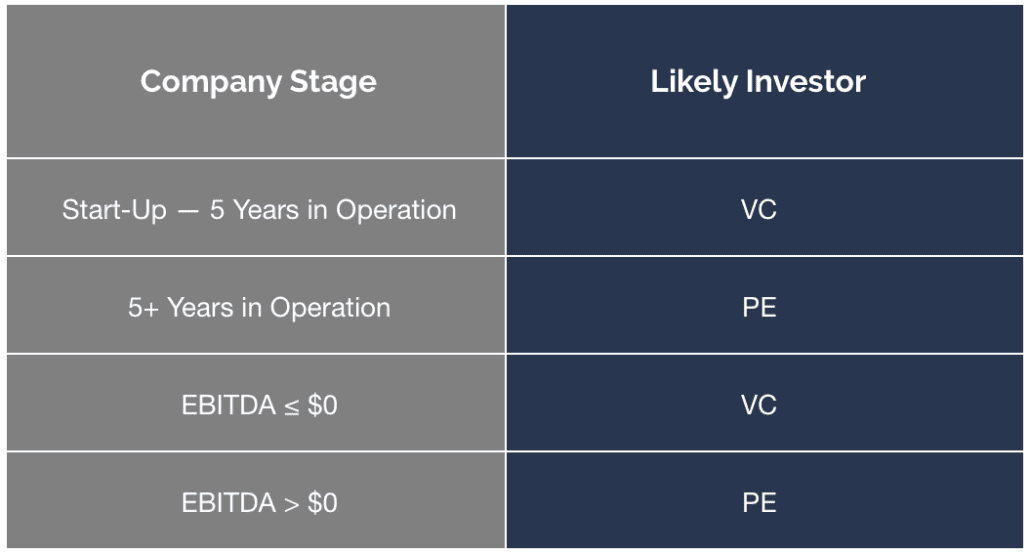

- Stage of company in which they invest. Perhaps the most universally applicable differentiator between VC and PE funds is the stage of company in which they invest. “Stage” can mean a lot of things but can generally be defined in terms of (i) length of time in operation and (ii) EBITDA – you either have it, or you don’t.

- Not to oversimplify things, but if your business falls somewhere between start-up and 5 years in operation, you are most likely a better target for venture capital. Said another way, if you are still raising capital in “rounds”, then you are squarely a target for the VC community. Further, if your company is producing revenue and growing quickly, yet you are not generating positive EBITDA because you have been investing heavily to support your growth and acquire new customers, then you are also a better fit for a VC fund. Of course, the inverse of these examples is true in that more time in operation and more profitability generally makes you a more relevant candidate for PE. See the table below to summarize these points:

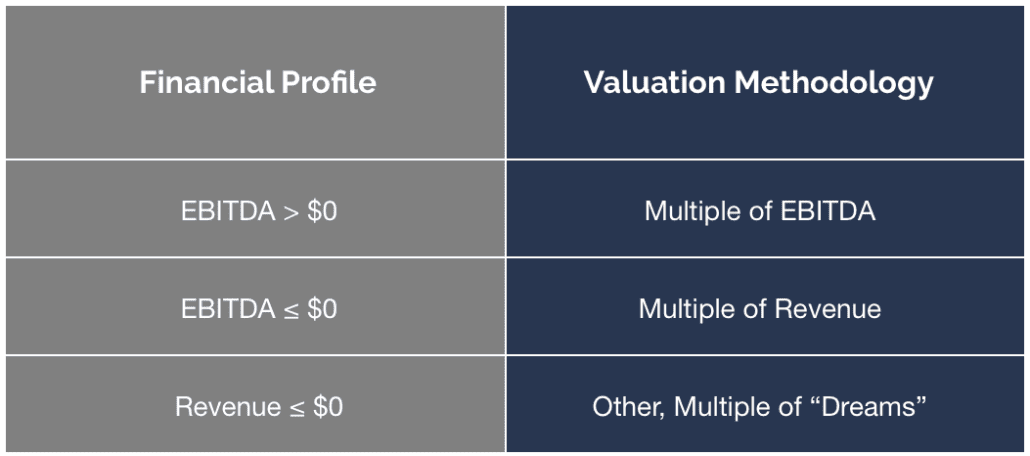

- How they approach valuing your company. A common PE methodology to valuing a business is to simply apply a multiple to last twelve months (or, “LTM”) EBITDA to arrive at an Enterprise Value. However, as noted above, not all businesses are generating EBITDA, so VC investors have developed methodologies to ascribe value to other metrics that can be indicative of a company’s worth. For instance, for fast growing companies that have revenue but no profits, one way to arrive at a valuation is to apply a multiple of revenue. This approach has become commonplace in sectors like the software industry (case in point, if you want to make a SaaS entrepreneur give you a funny look, then start talking about EBITDA multiples). It’s a strange paradox that, as the owner of a high growth business, it can be advantageous to not have EBITDA, because as soon as you generate profits investors will change their thinking from revenue multiples to EBITDA multiples. The exercise is even further complicated when a business is pre-revenue – I’ve spoken with one VC who humorously suggests that in this case you apply a “multiple of dreams”. The table below outlines this basic idea:

- Amount of capital invested per deal / number of investments made. While the total amount of capital under management between a PE and VC firm may be similar, it’s often the case that the amount invested per deal is higher for PE firms than VC firms. As a result, a PE firm will typically have a more concentrated portfolio of companies, say 10 or fewer investments in a given fund, as compared to a VC that may have 20-40 (or more) per fund. The chart below provides an illustrative visual example of this dynamic.

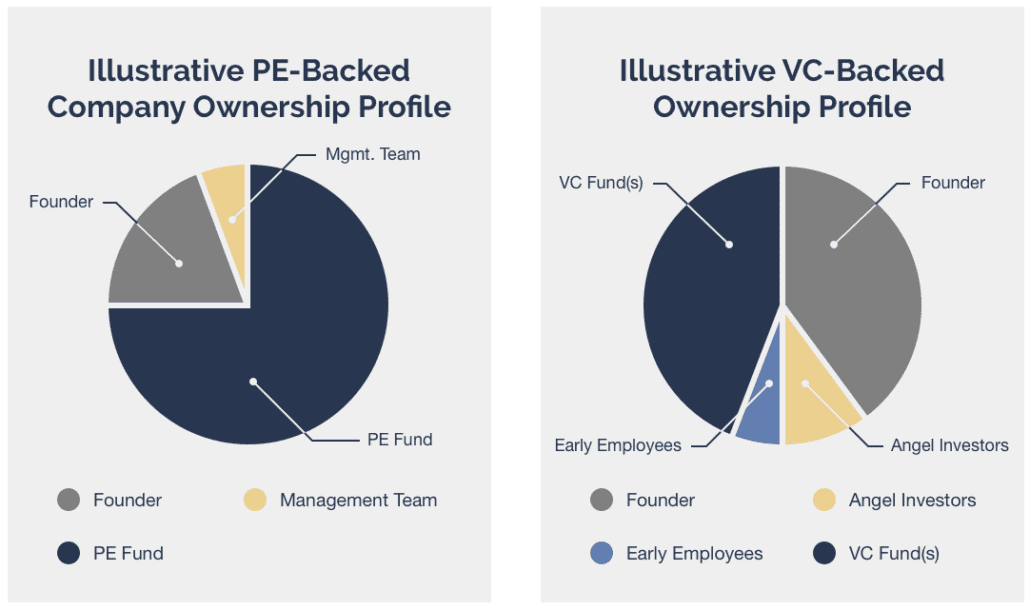

- Ownership position taken. In short, PE funds usually need control and VC funds don’t. For a PE fund, though, control doesn’t always mean 100% ownership. This is a common misconception. For example, many private equity funds insist that a company’s existing shareholders retain equity alongside them (or, “rollover”) such that the executive team has “skin in the game” as well. But, why do PE funds prefer control in the first place? There are various reasons for this, but an important one is that many successful PE funds have a proven track record of adding value to their portfolio companies by actively helping to guide strategy. All things equal, it’s much easier to influence an investment if you are the final decision maker – if you are a business owner reading this, you can appreciate the concept. PE funds also seek control given that they are typically writing relatively large checks into each deal as a percentage of their total fund size, and one way to offset the risk of such exposure is to have more say regarding how a business is managed (though most funds would freely admit that they would prefer to leave day-to-day management to their executive teams). Note also that in a private equity deal the number of investors is usually limited to the PE fund, a small group of prior controlling shareholders and the company’s management team.

- Conversely, VC funds are more comfortable with non-control, or “minority” investments because they are making far more bets than a PE fund (i.e. less of their fund is at risk per investment) and are not often set up for the requisite oversight of such a large portfolio of companies. Further, VCs are inclined to let a visionary founder retain control and continue to rapidly grow his/her business in advance of an IPO or sale once they’ve achieved critical mass. At this stage of investing, it’s important that the founder remains highly motivated with the accompanying entrepreneurial freedoms necessary to continue their growth trajectory. Finally, another departure from PE is that the ownership group in a VC-backed company will often include additional parties such as other VC funds, angel investors and early employees who knowingly traded lower compensation for equity upside.

- Here’s a chart that will help you think about the composition of shareholders in PE- and VC-funded deals:

- How they’ll seek to exit their investments. Once a PE fund has increased profitability to a point where an exit will likely produce an acceptable return, they will explore a sale to return capital to their investors. Today, private equity funds are exiting to two primary categories of buyers: (i) other private equity funds, and (ii) strategic buyers (i.e. larger corporate entities in the same or similar industry as the target company). While IPOs are a possibility if a PE firm’s portfolio companies achieve a suitable size, a sale to another PE fund or strategic buyer is often a more familiar path, results in fewer transactional intricacies and allows for a more complete exit.

- While VC funds have the same exit options as PE funds in the form of sales to PE funds and strategic buyers (and frequently utilize them), they are relatively more inclined to tap the public markets for exits via an IPO. VCs have historically gravitated to IPOs due to the ability to achieve premium valuations relative to other exit alternatives and their effectiveness in raising a large amount of capital at one time. IPOs also offer an ancillary, marketing-related benefit of raising awareness of the target company in connection with its public offering.

- In case you’re interested, here’s a chart that shows the “Top 25 VC-Backed Exits of All Time”. Are you familiar with the term “Unicorn”? In a business context, it refers to any VC-backed company that achieves a $1BN or more valuation. So, consider these success stories best in breed:

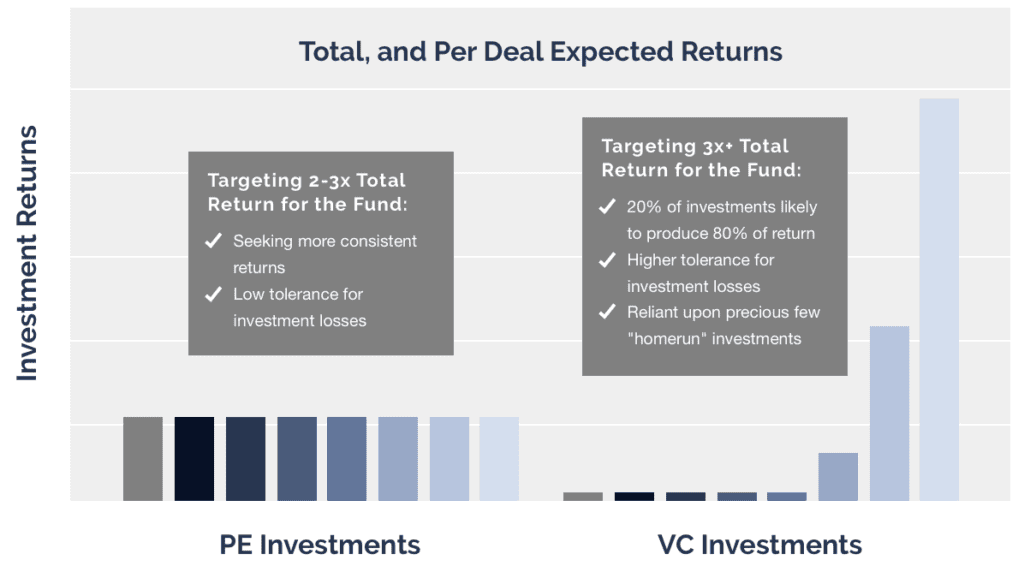

- Returns expectations. This is an area where we see a big divide in how PE and VC firms approach investing. PE funds are generally targeting a 2-3x return on each deal whereas VC investors have grown to accept that a mere 20% of their investments will produce 80% of their targeted returns. In other words, VCs know that many of their investments will not return anything, though a select few will be huge homeruns, on the order of 10, 50 or even 100x+ returns. Interestingly, though, that while the respective loss tolerances and upside potential for both strategies may differ, the expectations for a minimally acceptable return for the fund as a whole are not that far apart. Here’s a chart that puts this in perspective:

- Team backgrounds. Given the difference in the stage at which PE and VC firms get involved with their companies, the approach to staffing these firms can be different as well. For instance, it’s common for VC fund investment professionals to have significant entrepreneurial and operating experience with tech-related businesses. This experience can be important to position themselves as value-added investors and in their ability to relate to the founders of companies in which they are investing.

- In private equity funds, professionals will often come from the ranks of management consulting and/or investment banks, though certain PE firms do have a more operationally focused orientation which can result in them attracting talent with operating experience as well. For private equity funds, having investors with an operating background can result in more empathetic interactions with the executives running their portfolio companies and the ability to add value beyond financial engineering. Regardless of background, any investor with whom you’ll be working will be highly focused on helping you increase the value of your business.

Summary

I realize I just threw a lot at you, so here’s a side-by-side comparison of they key differences between PE and VC. Please get in touch if you’d like to discuss anything in this piece further, and consider us a resource to you and your business.

About ClearLight Partners

ClearLight is a private equity firm headquartered in Southern California that invests in established, profitable middle-market companies in a range of industry sectors. Investment candidates are typically generating between $4-15 million of EBITDA (or, Operating Profit) and are operating in industries with strong growth prospects. Since inception, ClearLight has raised $900 million in capital across three funds from a single limited partner. The ClearLight team has extensive operating and financial experience and a history of successfully partnering with owners and management teams to drive growth and create value. For more information, visit www.clearlightpartners.com.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this blog are solely my own and do not necessarily reflect any ClearLight opinion, position, or policy.